The mobile TV platform seemed to have it all. Why did it lose everything?

Last week mobile TV platform Quibi announced plans to shut down operations, just seven months after a promising debut. In its brief run, Quibi burned through $1.7 billion of investor goodwill, flubbed a turn on the Super Bowl ad stage and generally failed to live up to Valleywood hype.

On paper Quibi was a hit. Its premise seemed smart: snackable programming, or “Quick bites” as the clever portmanteau suggests. TV for the smallest of screens, targeting on-the-go viewers short on patience for full-length shows. Waiting for the bus? Stalled at Starbucks? Bored senseless at swimming practice? Cue Quibi.

Quibi’s parentage was the stuff of VC dreams. Big-name talents like founder Jeffery Katzenberg and former eBay and HP CEO Meg Whitman lent an air of certainty. The Quibi team delivered access to top studios, seasoned production pros and the brightest stars. And that $1.7 billion.

So, what happened? In a quick bite: Quibi fumbled the three factors needed to bring about change in user behavior.

The science of behavior change

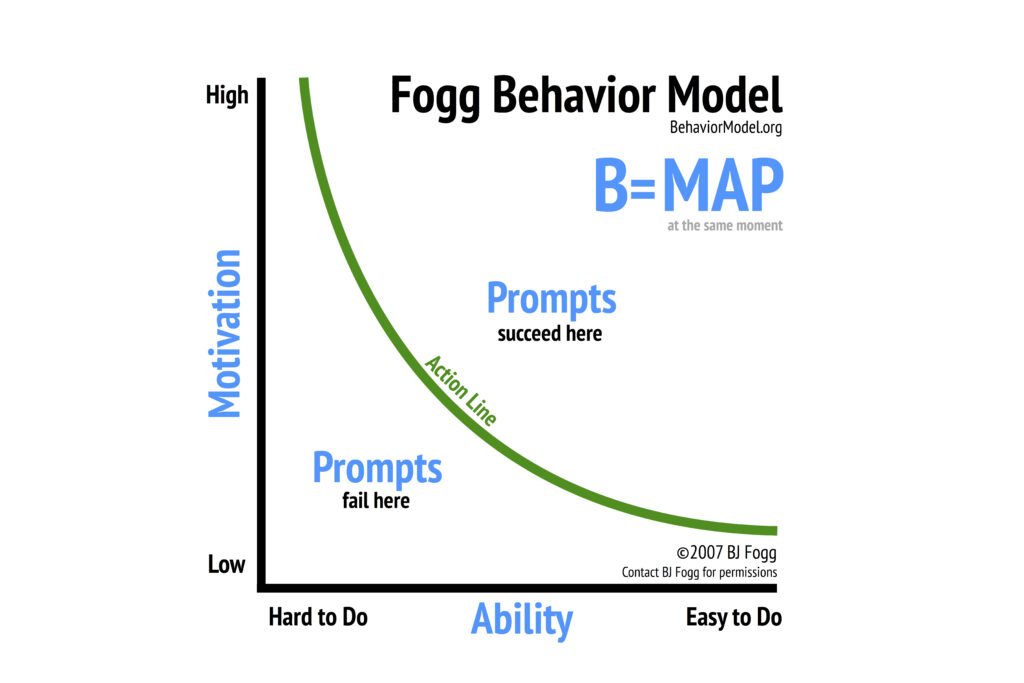

It’s no secret Quibi had problems from the start. Those issues become even clearer when viewed through the lens of behavior change. One of the most influential frameworks in the science of understanding human behavior is the Fogg Behavior Model (FBM) created by Stanford researcher BJ Fogg. By applying the FBM to the Quibi story, we can learn much about what ailed the platform and how to avoid similar missteps in future product planning.

The FBM is made up of three primary factors — Motivation, Ability, and a Prompt (MAP). To bring about behavior change, these factors must be present in sufficient quantity, and must converge at the same time. In FBM terms, Quibi needed to use the MAP elements to skillfully move prospective customers up and across the action line.

Because the desired behavior (people watching Quibi) did not occur, the FBM suggests Quibi whiffed on at least one of the three MAP elements. Let’s figure out where Quibi fell short.

Motivation: getting people to do hard things

In the FBM, motivation is defined as the reason for action. Motivation ranges from high to low, expressed as pairings of pleasure/pain, hope/fear, and social acceptance/rejection. For any brand that promises to entertain, motivation should center on pleasure. In Quibi’s case, the joy of a quick escape from the everyday. Quibi also needed to motivate users based on belonging and acceptance. For Quibi to scale, word-of-mouth virality was essential. Quibi needed shows people would remember, find relevant and use as social currency to help spread the word.

To drive adoption of the new platform, high behavioral motivation was a must but upstart Quibi never achieved it. Many reviewers have noted that Quibi’s content was just not that entertaining. Yes, the big-name stars were there. But studios short-sheeted Quibi with material off the cutting room floor. Shows failed to catch on and never really stood a chance against the Netflix, Disney+, Amazon Prime and Hulu offerings viewers were already paying for. Making matters worse, early versions of Quibi offered no way for users to share content with friends, stymieing growth on social media. Quibi failed to offer sufficient motivation for people to switch.

Ability: providing the means to act

Quibi gets slightly higher marks on the second FBM factor: ability. With a mobile content delivery value proposition, Quibi promised easy access to TV no matter your location in space and time. Anyone Quibi cared to have as a customer already owned a smartphone. (Score one for Quibi.) Quibi also improved on the standard means of delivery, investing in a technology called Turntable to make mobile TV-watching easier. Turntable seamlessly adapts the video display to match the orientation of the device as it changes position. In portrait mode, you see close-ups. In landscape mode, the wide shot. Quibi even worked with directors and editors to optimize video for Turntable.

But while Quibi was aiding users’ ability to watch TV, it was hampering access in other ways. Quibi chose a subscription-based model over the much more common ad revenue model. That meant it needed viewers to not only discover its brand, download its app, register and begin watching but also to subscribe at either a $5 or $8 monthly payment level. Turns out, none of what Quibi offered could overcome its demotivating subscription fees. Compared to the eons of free YouTube and other social media content viewers were happily consuming, Quibi was a non-starter. Quibi made TV watching harder to do, not easier. So while Quibi provided some enhancements to the viewing experience, it failed to change established habits.

Prompt: triggering action now

While the platform struggled with user motivation and ability, the third FBM factor — a prompt — was Quibi’s real downfall. Quibi launched in April 2020, just as the pandemic was upending public life. With no buses to wait for and no Starbucks to wait in, the impromptu moments Quibi had built its business around vanished virtually overnight. Sure, users could watch quick bites at home in lockdown but with uncertain job prospects and large flat screens already beaming Netflix non-stop, few were willing to pay for a new service that suddenly seemed both redundant and out-of-step with the new normal.

It’s unfair to fault Quibi’s leadership for failing to anticipate a global pandemic. Yet the platform’s self-imposed user experience shortcomings left the company exposed to new headwinds. Quibi needed to move users above the FBM action line. Instead it fell short because it couldn’t provide them with the convergence of motivation, ability and a prompt needed to change their behavior in Quibi’s favor.

So the next time you’re wondering if your product has what it takes to change human behavior, think of Quibi and the factors that conspired to keep its users below the action line, comfortable in old habits and resistant to change.

Explore our Digital Strategy practice to learn how we help clients understand users to create the next generation of digital businesses, products and services.