Cryptocurrency continues to grow, and Perficient is committed to helping financial services clients continue to understand and navigate this fast-changing part of the economy. Over the last 90 days, we have let clients know about the federal banking regulators planned cryptocurrency road map, explained what steps national banks need to take to begin crypto activities, provided thoughts on the possibility of a U.S. Bank Digital currency, and recapped the Acting Comptroller of the Currency’s speech regarding crypto regulation at the British-American Business Transatlantic Finance Forum Executive Roundtable.

Now, we will share and analyze the findings made by researchers Gordon Liao and John Caramichael at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Liao and Caramichael set out to analyze three plausible frameworks in which reserve-backed stablecoins see widespread adoption in the financial system. The NY Fed conducted this research on stablecoins as the circulating supply of stablecoins jumped fivefold to nearly $130 billion (as of September 2021).

Framework 1: “Narrow bank”

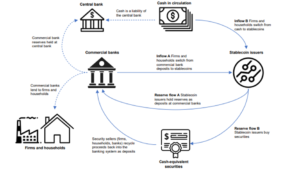

Liao and Caramichael defined a narrow banking framework as one in which stablecoin issuers are required to back their stablecoins with central bank reserves.

They found that this scenario would minimize the risk of “runs” on stablecoins but could also potentially reduce credit intermediation and, more significantly, would pose a large risk to credit provision (depending on the source of inflow). If stablecoins replaced cash on the American household and firms’ balance sheet, the influx of cash would result in a pass-through increase in the commercial bank balance sheet and the commercial bank’s reserves. The net effect is that the commercial bank balance sheet expands, but there is no change in credit being provided.

From a Federal Reserve balance sheet perspective, just as the various expanded the Fed’s balance sheet, the narrow bank approach could lead to an unplanned and uncontrolled expansion of the central bank’s balance sheet to accommodate the demand for reserve balances from stablecoin issuers in addition to commercial banks.

Liao and Caramichael concluded that a narrow bank stablecoin framework could bring the most stability, but at the potential cost of credit disintermediation in challenging economic times.

Framework 2: Security holdings

This framework would require cash-equivalent securities to be held as reserved collateral for stablecoins. If the stablecoin issuer is sourcing securities from commercial banks and selling the stablecoins to consumers, commercial banks are forced to reduce the size of their balance sheet to make up for fewer deposits from consumers – whether by reducing their own security holdings or reducing loan balances. Of course, in this instance, the money multiplier of bank deposits and loan balances is eliminated, so the economic impact would be negative.

Framework 3: Two-tiered intermediation

Liao and Caramichael define a two-tiered intermediation framework as one in which stablecoins would be backed by commercial bank deposits that are used for fractional reserve banking. In effect, stablecoins would be the same as current demand deposits. Liao and Caramichael also highlight the possibility that commercial banks issue stablecoins or provide tokenized deposits that are used for fractional reserve banking. Compared to the first two scenarios, a two-tiered banking system can both support stablecoin issuance and maintain traditional forms of credit creation.

Under this framework, even large inflows into stablecoins would have a neutral or even positive impact on credit provision. When cash is exchanged for stablecoins, whether at the firm or consumer level, and when commercial banks engage in fractional-reserve banking with stablecoin deposits, their balance sheet expands with expansions in credit, and security holdings account for most of the expansion. The Fed shrinks its balance sheet, as reserves increase slightly while cash liabilities decrease significantly. Households accumulate more assets, funded by the expansion in bank loans. The effect on credit provision is positive, which leads to a stronger economy in the real world.

Under this “Goldilocks Framework,” the regulatory treatment of stablecoin deposits is as the same as non-stablecoin deposits in terms of the required reserve ratio, liquidity coverage, and other regulatory and risk limits. Although not stated, FDIC insurance of stablecoin deposits would almost have to be required.

Further Reading

Readers of this blog may access the full 26-page research paper, without a paywall, here.