Are you tired of hearing about artificial intelligence yet? Well, I have some bad news. It’s only going to become the most important thing in our lives. Every once in a while you read an article that completely changes and overwhelms the way you think about something. Today, for me, it was The Artificial Intelligence Revolution: Part 1 and Part 2.

These are very long articles, so I have taken the liberty of extracting the best parts for a quick skim. If these excerpts get your gears moving, please, read the full articles.

Here is the best of Part 1:

First, the article describes the concept of accelerating progress, and why it is hard for us to accurately predict how much things will advance in the future:

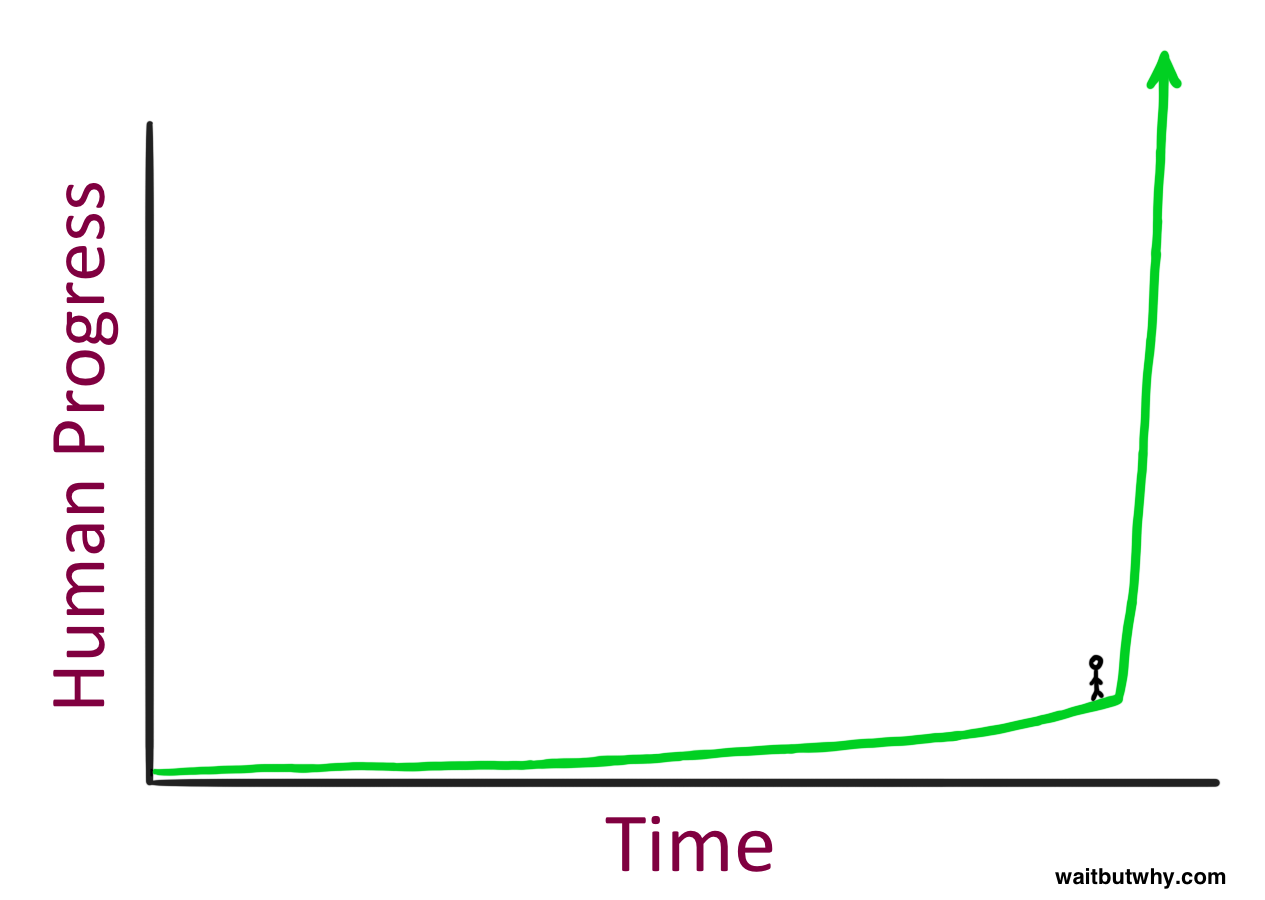

What does it feel like to stand here?

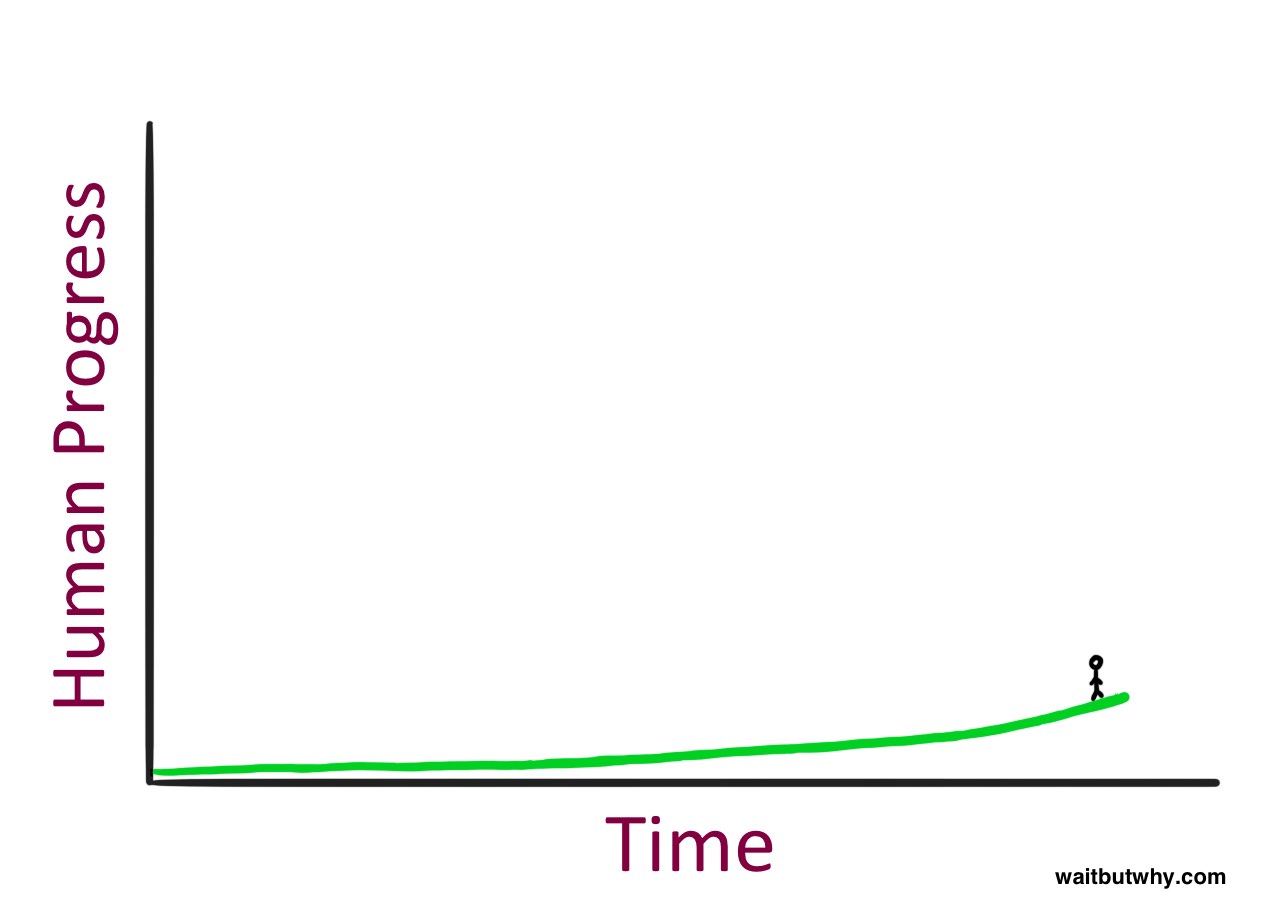

It seems like a pretty intense place to be standing—but then you have to remember something about what it’s like to stand on a time graph: you can’t see what’s to your right. So here’s how it actually feels to stand there:

Which probably feels pretty normal…

Human progress moving quicker and quicker as time goes on—is what futurist Ray Kurzweil calls human history’s Law of Accelerating Returns. This happens because more advanced societies have the ability to progress at a faster ratethan less advanced societies—because they’re more advanced.

The average rate of advancement between 1985 and 2015 was higher than the rate between 1955 and 1985—because the former was a more advanced world—so much more change happened in the most recent 30 years than in the prior 30.

Kurzweil believes that the 21st century will achieve 1,000 times the progress of the 20th century.

When it comes to history, we think in straight lines. When we imagine the progress of the next 30 years, we look back to the progress of the previous 30 as an indicator of how much will likely happen.

It’s most intuitive for us to think linearly, when we should be thinking exponentially.

In order to think about the future correctly, you need to imagine things moving at a much faster rate than they’re moving now.

We base our ideas about the world on our personal experience, and that experience has ingrained the rate of growth of the recent past in our heads as “the way things happen.”

When we hear a prediction about the future that contradicts our experience-based notion of how things work, our instinct is that the prediction must be naive.

If we’re being truly logical and expecting historical patterns to continue, we should conclude that much, much, much more should change in the coming decades than we intuitively expect.

The article then describes what Artificial Intelligence is and why it is a confusing subject to many people:

There are three reasons a lot of people are confused about the term AI:

AI sound a little fictional to us.

AI is a broad topic … AI refers to all of these things, which is confusing.

We use AI all the time in our daily lives, but we often don’t realize it’s AI.

John McCarthy, who coined the term “Artificial Intelligence” in 1956, complained that “as soon as it works, no one calls it AI anymore.” Because of this phenomenon, AI often sounds like a mythical future prediction more than a reality.

So let’s clear things up. First, stop thinking of robots. A robot is a container for AI, sometimes mimicking the human form, sometimes not—but the AI itself is the computer inside the robot.

Humans have conquered the lowest caliber of AI—Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI)—in many ways, and it’s everywhere. The AI Revolution is the road from ANI, through Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), to Artificial Superintelligence (ASI).

Artificial Narrow Intelligence is machine intelligence that equals or exceeds human intelligence or efficiency at a specific thing.

While ANI doesn’t have the capability to cause an existential threat, we should see this increasingly large and complex ecosystem of relatively-harmless ANI as a precursor of the world-altering hurricane that’s on the way.

As Aaron Saenz sees it, our world’s ANI systems “are like the amino acids in the early Earth’s primordial ooze”—the inanimate stuff of life that, one unexpected day, woke up.

Next, the article discusses why it it so hard to progress from Artificial Narrow Intelligence to Artificial General Intelligence – or something as smart as a human across the board, not just at one thing:

Nothing will make you appreciate human intelligence like learning about how unbelievably challenging it is to try to create a computer as smart as we are.

Hard things—like calculus, financial market strategy, and language translation—are mind-numbingly easy for a computer, while easy things—like vision, motion, movement, and perception—are insanely hard for it. Or, as computer scientist Donald Knuth puts it, “AI has by now succeeded in doing essentially everything that requires ‘thinking’ but has failed to do most of what people and animals do ‘without thinking.’”

To be human-level intelligent, a computer would have to understand things like the difference between subtle facial expressions, the distinction between being pleased, relieved, content, satisfied, and glad, and why Braveheart was great but The Patriot was terrible.

One thing that definitely needs to happen for AGI to be a possibility is an increase in the power of computer hardware. If an AI system is going to be as intelligent as the brain, it’ll need to equal the brain’s raw computing capacity.

Kurzweil suggests that we think about the state of computers by looking at how many calculations per second (cps) you can buy for $1,000. When that number reaches human-level—10 quadrillion cps—then that’ll mean AGI could become a very real part of life.

We’re currently at about 10 trillion cps/$1,000, right on pace with this graph’s predicted trajectory:9

So the world’s $1,000 computers are now beating the mouse brain and they’re at about a thousandth of human level. This doesn’t sound like much until you remember that we were at about a trillionth of human level in 1985, a billionth in 1995, and a millionth in 2005. Being at a thousandth in 2015 puts us right on pace to get to an affordable computer by 2025 that rivals the power of the brain.

Second Key to Creating AGI: Making It Smart. The truth is, no one really knows how to make it smart.

1) Plagiarize the brain.

As we continue to study the brain, we’re discovering ingenious new ways to take advantage of neural circuitry.

Remember the power of exponential progress—now that we’ve conquered the tiny worm brain, an ant might happen before too long, followed by a mouse, and suddenly this will seem much more plausible.

2) Try to make evolution do what it did before but for us this time.

Building a computer as powerful as the brain is possible—our own brain’s evolution is proof. And if the brain is just too complex for us to emulate, we could try to emulate evolution instead.

Over many, many iterations, this natural selection process would produce better and better computers.

3) Make this whole thing the computer’s problem, not ours.

The idea is that we’d build a computer whose two major skills would be doing research on AI and coding changes into itself—allowing it to not only learn but to improve its own architecture.

Soon, computers will be equals with humans, right? Well, there’s a problem. They will quickly become better than us. Turns out humans are not as powerful as computers could be:

The brain’s neurons max out at around 200 Hz, while today’s microprocessors run at 2 GHz, or 10 million times faster than our neurons.

The brain’s internal communications, which can move at about 120 m/s, are horribly outmatched by a computer’s ability to communicate optically at the speed of light.

The brain is locked into its size by the shape of our skulls, and it couldn’t get much bigger anyway

Computer transistors are more accurate than biological neurons, and they’re less likely to deteriorate

Unlike the human brain, computer software can receive updates and fixes and can be easily experimented on.

AI … wouldn’t see “human-level intelligence” as some important milestone … and wouldn’t have any reason to “stop” at our level.

It’s pretty obvious that it would only hit human intelligence for a brief instant before racing onwards to the realm of superior-to-human intelligence.

Just after hitting village idiot level and being declared to be AGI, it’ll suddenly be smarter than Einstein and we won’t know what hit us:

And what happens…after that? An Intelligence Explosion

I hope you enjoyed normal time, because this is when this topic gets unnormal and scary, and it’s gonna stay that way from here forward.

So, now things start getting very interesting:

And here’s where we get to an intense concept: recursive self-improvement.

These leaps make it much smarter than any human, allowing it to make even bigger leaps. As the leaps grow larger and happen more rapidly, the AGI soars upwards in intelligence

There is some debate about how soon AI will reach human-level general intelligence. The median year on a survey of hundreds of scientists about when they believed we’d be more likely than not to have reached AGI was 2040

That’s only 25 years from now, which doesn’t sound that huge until you consider that many of the thinkers in this field think it’s likely that the progression from AGI to ASI happens very quickly.

It takes decades for the first AI system to reach low-level general intelligence, but it finally happens. A computer is able to understand the world around it as well as a human four-year-old. Suddenly, within an hour of hitting that milestone, the system pumps out the grand theory of physics that unifies general relativity and quantum mechanics, something no human has been able to definitively do. 90 minutes after that, the AI has become an ASI, 170,000 times more intelligent than a human.

In our world, smart means a 130 IQ and stupid means an 85 IQ—we don’t have a word for an IQ of 12,952.

Yeah. Interesting.

Part 2 coming soon…