Key Points from Interview with Stefan Weitz

In this interview Stefan outlines the key areas where Bing sees itself diverging from Google. The discussion provides a clear and direct look at the way Bing plans to build its market share over time. There are three major components to Bing’s strategy:

- Become a personal assistant for the searcher, one that knows enough about you to highly customize the search experience (see the discussion about Mission Impossible below)

- Move away from a search box and make it totally transparent (for more on this read the discussion of the Xbox Kinect below)

- Focus on partnerships instead of acquisitions, allowing Bing to leverage the creativity and accumulated data of others

Stefan also sees great algorithmic search as “table stakes”, but that the real value add in the future is come through additional layers built on top of the raw algorithmic piece. These layers will handle the personalization, the embedding in different platforms, managing partnerships, etc.

This summary covers the basics. Please read the full interview transcript to get the full impact of the discussion.

Full Interview Transcript

Eric Enge: During our last interview we talked Google being very algorithm-focused, and how Bing was going to take a different path. I suspect that this divergence is beginning to grow. Is that right?

There is this shift in how we view the web and what it can do and the way Google does …

Stefan Weitz: Yes. Let me take you a step back, and cover some new stuff we haven’t talked about before. This bifurcation you referred to is happening. There is this shift in how we view the web and what it can do and the way Google does, and neither of them by the way are bad and they both are necessary, but there is a difference. They have done great work focusing on index size, index freshness, speed optimizations, and user experience models. They offer a great keyword search experience, and that’s good. On our side we obviously have to do an amazing job with that core index, with retrieval of URLs based on two and a half keywords per query.

… in many cases we actually outperform Google for algorithmic search and in almost all cases we are at least as good or better.

All that stuff is table stakes, and we’ve always known that. With a couple of our more recent algorithmic updates, in many cases we actually outperform Google for algorithmic search and in almost all cases we are at least as good or better. But, there is this new thing, this notion that the web itself has changed and continues to change at an accelerating pace.

Search really is predicated on the structure of the web, and as it changes, search needs to change with it. Over time search looks less and less like a search box on a web site. It looks much more like a service, almost like a platform that spans across any input modality from a gesture on your Xbox, to voice on your phone, to touch on a tablet device, to even implicit queries that you don’t even know necessarily are happening on your behalf.

Search really is predicated on the structure of the web, and as it changes, search needs to change with it. Over time search looks less and less like a search box on a web site. It looks much more like a service, almost like a platform that spans across any input modality from a gesture on your Xbox, to voice on your phone, to touch on a tablet device, to even implicit queries that you don’t even know necessarily are happening on your behalf.

Of course, the service has to be personally useful. We want to create something that takes into account who you are, who you know, what you do, all those types of things, and then focuses on delivering experiences that help turn those ideas of things you want to actions. To do this well, we have to do an amazing job of brokering resources from all across the web to enable new levels of functionality.

In our view, search will start to be less about the traditional keyword to URL model, although we know we have to do that extremely well, because that’s what folks expect today. But, we see both the fun and innovation is around this notion of a horizontal service that can span across all of our properties, across other people’s properties, and across all devices and input methods that literally allow people to make the best use of the web that they can, given who they are, where they are, what they want to get done.

Eric Enge: Part of what you are talking about a distribution of search, so instead of going to a place to search, search is where you are already.

Today you are in the flow of doing something, and you have to stop and shift and go do a search.

Stefan Weitz: Exactly, it will be ubiquitous. Today you are in the flow of doing something, and you have to stop and shift and go do a search. This is similar to what it used to be like to connect to the Internet. You used to have to “dial up” the Internet. Today it is always available and you don’t have to think about it. We believe the same transition will happen with search. You will no longer have to think about taking some actions to do it because it will be embedded in the flow of what you are already doing, right where you are already.

In addition, search is much bigger than one single entity.

In addition, search is much bigger than one single entity. A lot of what people are looking for resides in other services and databases that are not readily available online. We are working hard to develop access to that information by setting up partnerships with other companies and acting as a universal broker to integrate that content directly into search.

Eric Enge: Can you help illustrate this concept with an example scenario?

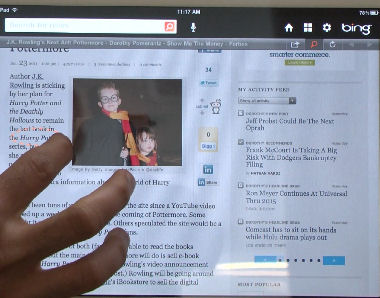

Stefan Weitz: Sure. One I like a lot is a feature in the Bing iPad application called Lasso. When a user views a page, they can just take their finger and circle something. The act of you circling it gives us some intent cues. Let’s say they circled Mission Impossible. We then do a re-query, and use all of the power of Bing’s backend to analyze it. We know that Mission Impossible is a movie, and movies have attributes like show times, reviews, trailers, pictures, and casts. We return back in the iPad interface this really beautiful page that has all these components that describe the movie right there so you can take action.

|

You can click a button, buy a ticket, and see the restaurants around there. That’s a really simple example of where we are taking this notion of integration, where we recognize the context of your action, circling something on the device, and then build an experience on the fly that has all the information and services in the right place so you can actually do something.

As you begin to think through how that could evolve, it gets a little more interesting. There are actually four Mission Impossible movies. There is also the TV series, and video games, and all sorts of books. Traditionally, what search is going to do is going to look at those keywords, and attempt to use static rank and figure out what the most relevant Mission Impossible link would be for most people. It might assume that the most relevant result is one of the older ones because it has more static rank to it than the brand new movie.

In our example, perhaps the page is talking about the latest Mission Impossible (MI) film. The opportunity for us is to take the global context of that page (what the overall page is talking about), the engine should know that what I am really asking for is the latest Ghost Protocol film, not Mission Impossible 1, or the series from the sixties or Peter Graves or anything else.

|

That’s the first level of understanding more of the context behind the query, in this case, me circling that MI link. Next is to start thinking about all the different things that I can actually do, and that’s where this notion of experiences and actions come into play. Perhaps the engine knows that I’ve rented Mission Impossible #1 and #2 from Netflix, and it can then makes the suggestion that I want to see #3 before I see #4. Next, it knows that I am in my office in Bellevue today, and my calendar says I am busy till four, and the most logical place to go see it might be the one closest to me at six.

The idea is to be far more intelligent about the things that I personally want to do based on the various signals available.

The idea is to be far more intelligent about the things that I personally want to do based on the various signals available. This gets away from this notion that all objects are the same to all people, and in this example it focuses on how I want to interact with this particular object given all the information the system knows about me.

Eric Enge: This is a permission-based system, where you share details about your intent, and you get a personal assistant in return.

Five years ago this would have sounded like science fiction, but now it’s fairly trivial to do …

Stefan Weitz: Yes. Five years ago this would have sounded like science fiction, but now it’s fairly trivial to do, but it requires a different view of the search experience.

Eric Enge: This is an extension beyond the original notion of becoming a decision engine because you are trying to add another layer of insight to it.

Stefan Weitz: One example that I used to use was the ability we developed to look at all the reviews on the web for a consumer device, such as a Smartphone. Say there were a thousand reviews of a device; we developed the ability to actually have machines read all those reviews, segment the reviews into what the reviews were about, and then apply sentiment analysis to see what they were saying. For example, we may determine that 48% of them had something positive to say about battery life.

… the emotional component of decision-making is in many cases more important than the rational one.

What we did is try to take all that data and make it into knowledge that people can use to decide to do something. That’s exactly where we began, but then just in the last year or so we began to look more at this notion of how people make decisions. I’ve done a lot of work with some neuroscience people out there, and then the research guys have done a lot of work as well to look at this. And, people like Jonah Lehrer, who is a great neuroscientist, talk a lot about the fact that the emotional component of decision-making is in many cases more important than the rational one.

What we did is try to take all that data and make it into knowledge that people can use to decide to do something. That’s exactly where we began, but then just in the last year or so we began to look more at this notion of how people make decisions. I’ve done a lot of work with some neuroscience people out there, and then the research guys have done a lot of work as well to look at this. And, people like Jonah Lehrer, who is a great neuroscientist, talk a lot about the fact that the emotional component of decision-making is in many cases more important than the rational one.

The lizard brain inside the human cortex is the first place that gets invoked when you have some stressful decision to make. So, we began to look at this notion of how people make decisions. We had built rating tools, Bayesian model predictions for traffic, and all these really cool tools that we’ve built to help people rationally make decisions.

… we are actually literally bringing in that other critical piece of decision-making which is who you know, what they know, and how much you trust them.

I like to think of myself as a rationalist, but, it’s the other side, the right side of the brain that we were missing. That’s where a lot of the work with Facebook and Twitter and all the different social signals we are getting really comes in, to augment the ability for people to make decisions with Bing and to take action with Bing. It’s not just tools, but now we are actually literally bringing in that other critical piece of decision-making which is who you know, what they know, and how much we trust them.

Eric Enge: Can you see Bing collecting more information from people then what they give on Facebook and Twitter? Perhaps collecting profiles directly from the users?

Stefan Weitz: For years people have tried to collect profile data as you know. The number of people who actually opt to give that data is quite low, not because of privacy concerns, but just because they don’t see the value of it.

There is some more explicit stuff that we think we can do, but we are also very aware of the fact that people have been trying to do profiles on the web for fifteen years and have very limited success. It won’t work unless you can tie it back to some direct benefit that the user will see.

Eric Enge: Yes, because the person needs to take time to enter that information, and as we know in our wonderful world of the web, seconds are an eternity. Can you talk a little bit about the new arrangement with Twitter?

Going forward you’ll see more integration into the core search experience. We’ve been experimenting with what else you could do with Twitter.

Stefan Weitz: It really is an extension of what we had before. That being said, we did it because we value that data. We still use it to figure out when new things are happening, and that helps our news index find out what’s going on in that particular area. Going forward you’ll see more integration into the core search experience. We’ve been experimenting with what else you could do with Twitter.

Today we put it on a news page, for example, so when you are on a news article you might be reading about the latest Dell laptop, you can see relevant, de-duped, high quality tweets right in that page. So, you’ll see more of that type of thing from us rather than just paste it across all pages. We think there are cool things we can do by looking at what people are trying to do, and what decisions they are trying to make.

Eric Enge: Do you see yourself having an ability to extract information about the person to use in personalizing their search results from Twitter as well? For example, you may find out that they are currently looking at a trip to Rome because I asked three people on Twitter about that.

With adaptive search, we look at the queries you are issuing, understand the category of those queries, and then begin to re-rank future search results given the category.

Stefan Weitz: That’s a really good idea, I am not sure we’ve got that in our plan yet, but I can see how it might work though. One thing we released is this thing called adaptive search, and the reason I am bringing it up is because I can see how what you just said applies. With adaptive search, we look at the queries you are issuing, understand the category of those queries, and then begin to re-rank future search results given the category.

The tweets could work the same way where you have been tweeting a ton about your cocker spaniel, and then you search on “dog movies”, we might emphasize movies that have cocker spaniels in them. That might be the most bizarre example ever, but you get the idea.

Eric Enge: Now you’ve got Facebook and Twitter together, and that’s great. This smells like a shift away from having such a high level of algorithm focus and more towards people-oriented signals.

Stefan Weitz: That’s right. When you think about the initial algorithm it’s all static rank really does, and all PageRank really does, is use people to rank pages, because at the end of the day its people who contribute links, and people who use anchor text.

But now, links don’t have to be our only signal map. Now we can use the amazing social graph inside of Facebook and to an extent Twitter. And of course, even more important than just the connections of people to each other, it’s what I, Stefan am doing across the web on all of the different sites, not just on Facebook. It’s just marvelous.

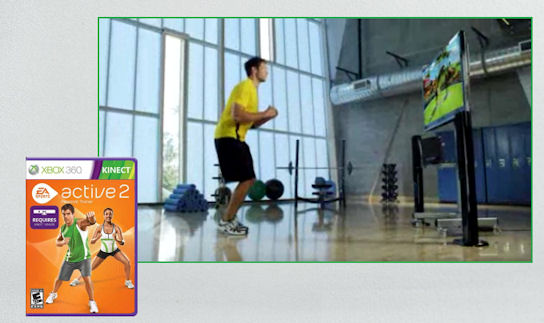

Eric Enge: Tell me a bit about Xbox Kinect.

It gets back to the core principles of Bing: a) Bing can be integrated everywhere, and b) there can be many different kinds of interfaces.

Stefan Weitz: I’ve been looking at voice recognition since I was a kid. The software used to be horrendously expensive, and the quality of the recognition was frankly not that good. But today, speech recognition is fairly good across mobile devices and across desktops; in fact, it’s stunning how good it is. The Kinect work is literally a revolutionary way to interact with a computing device. In Kinect, the device is controlled entirely by voice and your body movements. It gets back to the core principles of Bing: a) Bing can be integrated everywhere, and b) there can be many different kinds of interfaces.

|

The last thing I think that highlights really well is this notion of partnerships, and how we at Bing do a lot more partnerships than we do acquisitions.

The last thing I think that highlights really well is this notion of partnerships, and how we at Bing do a lot more partnerships than we do acquisitions. We look at partnerships as a way to accelerate the transition of search away from keywords to this more action-oriented model. Partnerships allow us to leverage the great content and tools being built by others. It also allows us a great deal of flexibility in combing the value of one third-party service with that of another third-party service to create something of much higher value.

Eric Enge: Can you talk a bit more about the mobile side of things?

Stefan Weitz: I was in New York a month ago. I walked into a little book store which had these amazing books, absolutely gorgeous, and there were many coffee table books, the big, huge, heavy $40 books that were far too big for me to carry on the plane although I am sure I would have tried if I had thought about it hard enough.

I had my phone with me and I actually just pointed my phone at the book I saw on twentieth-century architecture. Sure enough, my Windows Phone with the Mango OS found it, and showed me all the places I could buy it. I was curious if I could get it in Seattle because it was a huge heavy book. It showed me where I could do that, and it also offered me a way to buy it online from the shop I was standing in!

I had my phone with me and I actually just pointed my phone at the book I saw on twentieth-century architecture. Sure enough, my Windows Phone with the Mango OS found it, and showed me all the places I could buy it. I was curious if I could get it in Seattle because it was a huge heavy book. It showed me where I could do that, and it also offered me a way to buy it online from the shop I was standing in!

To do this the camera on the back of the phone had to understand what it was seeing. Then it kicked into the search system itself which understood it was a book, it understood the title of the book, and then it actually issued a query to Bing’s backend for shopping and found the places where I could buy it, and displayed them right there.

You have the same thing with the translation on the device, you can point at something, hit a button, and it translates it into twenty-three languages. You have the same with music in the device now. If you are sitting around and you hear something on, you can hit a button and boom, it tells you what the song is, how much it costs, and where you can buy it right away.

This new type of mobile functionality is awesome, because you always have it with you.

Eric Enge: Mobile often also comes with the context of being out of your office or house as well.

I think it also speaks to one of the big tenets of our vision which is that when you are using a phone or a tablet or a mobile device of some sort, the last thing you want to do is have to actually go search.

Stefan Weitz: A mobile device really is the most personal of personal computers because you often don’t share your device. All your contacts are in there, all your social networks are on there; you can get all your documents on there. Everything is on there, and it knows where you are, and you can let it know where you are going. I think it also speaks to one of the big tenets of our vision which is that when you are using a phone or a tablet or a mobile device of some sort, the last thing you want to do is have to actually go search. It just seems wrong, because likely you are doing something else at the time.

You want the device to be smart enough to be executing things on your behalf, and then doing things. If you are on Bing maps, for example, and you are trying to figure out where you are, you can tap on the little city icon on Mango, it’s called Local Scout. Local Scout fires up and shows nearby places to eat and drink, upcoming shows in the area, and attractions all around you. It’s like nineteen queries in one. It’s doing all these things, pulling them back based on where you are, what day it is, and all this different data at the search backend. This is search in context, and its way different than the traditional notions of search.

Eric Enge: It sounds like you have a core underlying algorithm, and then you have a whole layer on top of it which is the layer that adapts everything based on context. The context layer becomes the place where really the bulk of the added value lies. So, the layer at the bottom becomes a commodity.

Stefan Weitz: You are actually almost exactly right. There are a bunch of other services such as personalization, social services, and the actual broker service that understands what services exist on the web and how they can be used to help the person accomplish a task. There is the object service which understands that this thing is a book or this thing is a bottle of vitamin water, and what that means, and what you can do with it.

We actually just created a whole team under Brian MacDonald now that is focusing literally on that what you just said, not customization, but the dynamic experience given the intent, the context, and the access device.

We actually just created a whole team under Brian MacDonald now that is focusing literally on that what you just said, not customization, but the dynamic experience given the intent, the context, and the access device. For example, on a mobile device, you don’t want to display a bunch of links. It makes no sense because it’s a small screen.

We need to take all of those things into account, and then let the magic of Bing stitch all those services together into some experience that makes sense given all those different variables. That is where we are pushing the future of search at Bing.

Eric Enge: Thanks Stefan!

Stefan Weitz: Thank you Eric!

About Stefan

Stefan Weitz is a Director of Search at Microsoft and is charged with working with people and organizations across the industry to promote and improve Search technologies. While focused on Microsoft’s product line, he works across the industry to understand searcher behavior and in his role as an evangelist for Search, gathers and distills feedback to drive product improvements. Prior to Search, Stefan led the strategy to develop the next generation MSN portal platform and developed Microsoft’s muni WiFi strategy, leading the charge to blanket free WiFi access across metropolitan cities. A 13-year Microsoft veteran, he has worked in various groups including Windows Server, Security, and IT. Stefan is a huge gadget ‘junkie’ and can often be found in electronics shops across the world looking for the elusive perfect piece of tech. You can follow Stefan on Twitter