When outsourcing software development projects, comparing vendors with different price points can be very difficult. We propose variables that should be taken into account when deciding which vendor is most likely to produce the lowest Total Cost of Ownership for an offshoring or nearshoring development project. We also evidence why we believe Perficient Latin America is able to offer the lowest Total Cost of Ownership in relation to its peers in Latin America.

The term Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) was coined by the Gartner Group in 1987 to help buyers determine both the direct and indirect cost of a System[i]. Within software engineering, the term is understood to include the development, enhancement, maintenance and support costs for an application[ii]. Why is this concept so important?

The human mind inherently looks for the “path of least resistance” when making a decision. When it comes to pricing, the most immediate information available is “sticker price”. Thus, it is not surprising that many clients look for the vendor with the lowest rate chart.

We argue that “sticker price” is a misleading metric to use to choose a software services vendor. Unfortunately, other variables that better portray the value of a vendor are hard to convey, as they are often visible only to software practitioners with some experience, who are often forced to relegate a final purchasing decision to less informed financial (or purchasing) managers. As a consequence, organizations often use “hard good” criteria to buy software services (trying to fit a creative, customized software endeavor into a cookie-cutter price versus creating a technical specs mold).

We propose that a better way to choose a vendor should involve considering five key variables that determine, in great part, the Total Cost of Ownership of outsourcing a software development project:

·Process: For any project involving more than one resource, the success of the engineering initiative depends on how well the team works together. Hence, process (or the behaviors, methods, and practices that govern the way a group performs) becomes critical for the success of all but the smallest of software initiatives.

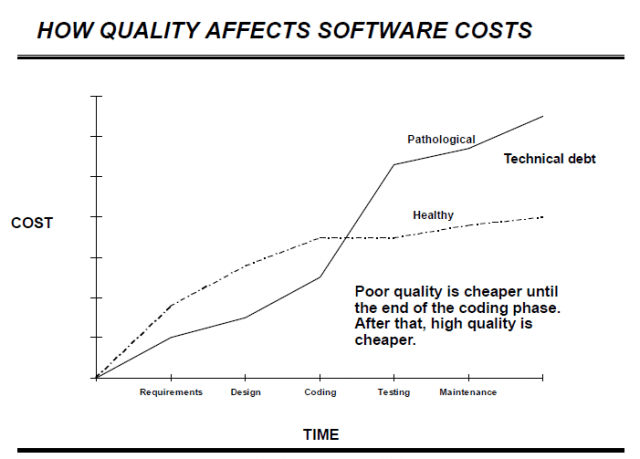

·Quality: Software is expensive to make and is typically built to last. An application that is hastily and shoddily coded will incur a technical debt[1] whose correction can very easily surpass, over the life of the application, the initial cost of building the application in the first place.

·Risk: Software has empirically demonstrated a significantly higher failure rate than other engineering endeavors. It has also been demonstrated that the risk of project failure decreases as the objective quality of the vendor increases. Hence, it might be cheaper to pay a “quality premium” to reduce risk, than to incur a lower upfront cost that entails a higher risk of failure.

·Productivity: In software, perhaps more than in any other engineering endeavor, the productivity between a great developer and a mediocre one may vary by a factor of 10 (some practitioners argue that even more). Salient differences in productivity thus relegate “sticker price” to a variable of secondary importance.

·Cost (as a total, and per unit of time): Taken at face value, cost is simply a price paid per unit of time (i.e. cost per hour or cost per developer per month). From the point of view of TCO, cost should take a long term perspective, and be accounted for throughout the life of the application.

Exploring the variables that impact TCO

To measure the impact of the above variables, throughout this article we refer to the numerous studies of Caper Jones, Chief Scientist Emeritus at Software Productivity Research (SPR) and perhaps the most renowned software productivity expert in the world[iii]. Professor Jones has recently examined the productivity of over 13,500 software projects undertaken in more than 650 companies within the US[2], giving his insights a solid knowledge base.

Process

Process is perhaps the highest level variable impacting TCO. It is so important that Jeff Sutherland, the inventor of SCRUM, has asserted how a well implemented agile process can lift the productivity of a software development group by a factor of four in terms of throughput[iv].

Broadly defined, a software engineering process describes the methods, activities, and techniques utilized to deploy and manage an engineering project. It describes as well the cultural, social, and behavioral rules that are directly or tacitly enforced during said project.

A good software engineering process impacts other TCO variables because it: a) produces quality software, b) instills a high level of commitment in the team, and c) significantly diminishes the risk of failure, and hence, d) lowers the overall cost of a software engineering initiative compared to a haphazard development environment.

Perficient Latin America is Latin America’s most experienced company in maintaining a formally recognized mature process (we have been continuously assessed at the highest level of CMMi 5 for over thirteen years). We are very serious and disciplined about “process” and value it for the results it delivers to clients. Indeed, we emphasize two aspects that truly make us a process-oriented company:

1) Even in an environment where 85% or more of our projects are SCRUM based, we maintain quantifiable hard facts about our engineering process. Because we believe that that which cannot be measured, cannot be improved, we retain company baselines on our productivity and quality at both an aggregate (company level) and granular level (per team member).

2) We are objectively replicable. By this, we mean that we have a high level of certainty that our performance in the past is a good prognostic of what we are capable of delivering in the future.

On the contrary, organizations without structured processes tend to proceed haphazardly, almost by “luck”. Often such organizations depend on “heroics” (late nights, an extremely talented individual) to produce results, and are prone to become “one hit wonders” that are not able to predictably replicate their wins.

Perficient Latin America is a system dependent company, meaning that we are able to replicate our good results in different types of initiatives, without becoming unduly dependent on individuals to drive success.

How is this relevant to TCO? Obviously, a process is not inherently good or bad, just predictable (bad processes produce bad results, good ones good results). However, without the discipline of process, a client is left wholly in the dark about what to expect from a vendor. Hiring an unpredictable vendor is like playing Russian Roulette. A bad draw can cost a company the budget for the project (we elaborate on this topic when touching upon the concept of risk in the second part of this article).

Culture is a fundamental ingredient of process. A company culture determines the attitudes people take with respect to challenges, openness of communication, sharing of information, process discipline, and dedication to a task. Without a solid culture, it is impossible to have a solid process.

At Perficient Latin America, we hire engineers as much for their technical ability as for their cultural fit with our organization. Day to day, we seek people who are: curious, open to feedback, open to sharing their knowledge with others, flexible and creative in their thinking. We also foster a culture that raises red flags early, understands that failures are a lesson, and knows that excellence is a path that requires effort, never a destination.

Quality

Poor code is fast to write. However, it often does not comply with standards, nor respects best technical practices. “Initial” development costs for an application that is hastily and shoddily written are lower. Yet, technical debt is incurred and, when it comes time for the deployment and maintenance of the application, its Total Cost of Ownership increases dramatically. Below is Caper Jones’ description of this reality, summarized in a graph[v]:

Optimizing the Total Cost of Ownership on an Outsourcing Software Development Project photo 1

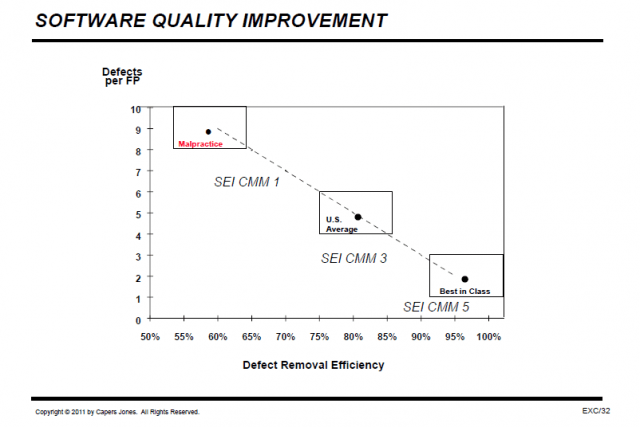

On the other side of the coin, studies reflect how companies with higher levels of process performance produce code with significantly more quality. In the comparison chart below (also from Caper Jones), CMMI level 5 companies submit approximately three times fewer bugs than organizations that, although still “mature” have not yet reached process excellence (i.e. those qualified as CMMi 3)[3],[vi].

Optimizing the Total Cost of Ownership on an Outsourcing Software Development Project photo 2

Perficient Latin America currently performs at world-class quality levels, injecting less than 1 defect per Function Point, on average[1], which would place it at a level at or above what Caper Jones considers to be “best in class” for CMMI level 5 organizations.

Now, the incremental cost of letting a bug “survive” in the code as the project life-cycle reaches its end, has been studied at length: that bugs detected after an application has been put into production are 10 to 20 times more expensive to fix than those detected during the early stages of the project (not to mention the collateral damage caused by a buggy application in the client’s hands).

In an average application (1,000 Function Points) setting up a test environment to fix a bug, finding the bug, and running final tests consumes upwards of 12 hours per bug. Multiply the number of defects by the estimated cost to fix them, and one finds a very significant burden for TCO bottom line.

For example: In a 1,000 FP project (approximately 23,500 effective LOC of Java code) one can expect a serious, committed and established software engineering organization (represented in the CMMI scale as a CMMI level 3) to display 118 bugs once the app is in production. · Correcting those bugs takes approximately 1,410 hours.· Under the same scenario, expected Field Error Rates at Perficient Latin America would expect the appearance of only 8 bugs once the app is in production. Obviously, the larger the application or set of applications deployed within a nearshoring relationship, the larger the savings one perceives from best-in-class quality.

We hope these insights help you when choosing an outsourcing software developer and investing in a partnership that has the potential to be long term. In the second part of this article, we will delve deeper into the three remaining key variables (risk, productivity, and cost) that determine the Total Cost of Ownership for outsourcing a software development project.

Continue reading part two of this article.

More on Perficient Latin America: Perficient Latin America is a nearshoring, 30-year-old IT services firm with offices in Colombia, Mexico, and the US that combines high-level process maturity with agile methodologies in order to reduce the Total Cost of Ownership of software development projects. Want to know more? Let´s start a conversation.

————————————

References

[1] Technical Debt, a term coined by Ward and Cunningham in 1992, is the assertion that quick and careless development that exhibits low-quality levels, results in many years of expensive maintenance and enhancements in the future.

[2] Including 150 Fortune 500 organizations, 35 government / military groups, more than 7 large universities, as well as several hundred medium or small organizations within the United States.

[3] Also noteworthy is the terrible performance of the so-called CMMi 1 organizations (labeled as “malpractice” in the chart, but also commonly labeled “immature or chaotic”).

[i] http://www.gartner.com/it-glossary/total-cost-of-ownership-tco/

[ii] As defined by Caper Jones in “Software Quality in 2012: A Survey of the State of the Art”.

[iii] http://www.amazon.com/Capers-Jones/e/B000APTHHW

[iv] http://leanmagazine.net/scrum/scrum-large-projects/

[v] As pictured in “Software Quality in 2012: A Survey of the State of the Art” by Caper Jones.

[vi] http://semat.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Capers_Jones.pdf

[vii] http://semat.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Capers_Jones.pdf