Andrew Tomkins is the Chief Scientist for Yahoo! Search. Andrew joined Yahoo! Research in 2005 from IBM. His research over the last eight years has focused on measurement, modelling, and analysis of content, communities, and users on the World Wide Web.

Prior to joining Yahoo! Research, he managed the “Information Management Principles” group at IBM’s Almaden Research Center and served as Chief Scientist on the WebFountain project. Andrew received bachelor’s degrees in mathematics and computer science from MIT and a doctorate in computer science from Carnegie Mellon University.

This interview expands upon the keynote presentation that Andrew gave at SES NY on the future of search. The presentation covered some very interesting ideas on how to improve the presentation of results within a search results page. The discussion relates to the initiative Yahoo referred to as “SearchMonkey”.

|

Interview Transcript

Eric Enge: In New York, you talked about the future of search, but the thing that really struck me in the conversation was the notion of “webmaster supplied content” communicated essentially directly to the search engine. Maybe you can tell me whether that notion resonates with you in just your general thoughts on the concepts that you laid out in the presentation?

Andrew Tomkins: I’ll start by saying that the characterization of webmasters and publishers sharing a more structured representation of their content is exactly what we are talking about. I guess it’s easy to think of it as sharing it with a search engine. We’ve talked about a few different pathways that publishers could use to share structured metadata.

But, I think of it more as just expanding the notion of publishing to a richer representation that is broadly for consumption by humans, as well as applications that will do something value added with it.

Eric Enge: Sure. Anybody can read the value added content.

Andrew Tomkins: We’ll receive a feed from a publisher and that will give us some content that we can use to help with how we present results from the publisher. Or, we will do the extraction of metadata on the fly from the publisher, if the publisher gives us information about a rule for how to do that, or we’ll consume markup. In a sense, markup is a very attractive approach here, it doesn’t make any assumptions about who is going to be consuming it. It could be vertical search engines, it could be third-party application developers.

The approach that we are taking is to be very standards compliant in the form of markup that we accept. That means it’s very easy for people to conform and people can start to begin adopting a uniform approach to what they put on their sites so that it pulls together different content across a lot of different places.

It’s pretty resilient as the ecosystem changes and evolves. If you have good markup standards and people have really been serious about adopting them, then you don’t really know where that’s going to happen as a result. It could be very transformative; it could open up whole new avenues for searching information discovery, just like browse, navigation and information content. Yahoo! see’s all of this as positive outcomes because the world will be a better place when that information is available. From the search standpoint, it’s one of the many channels that we can use to get this deeper understanding.

Eric Enge: Right. In your presentation, you said that this structured data will not influence rankings, but what it would influence is presentation; specifically what you show in a search result.

So, today the mechanism somebody might have to do that is basically the meta description tag, which might get used when you don’t distill your own description of a webpage from another source. But, now with this structured data from the publisher, you can actually have pretty different looking types of results.

Andrew Tomkins: Yes, that’s right. The abstracts that are displayed in search engines do several things at the same time. Sometimes, somebody has a question and you are looking for the answer and you can get it right off the search page. A much more common usage is that you want to consume the abstract in order to inform your decision about whether to pursue that resource.

We view this expanded metadata as helping in both cases. It might be that if the URL is actually the homepage of a restaurant, then you can embed the address, the phone number and the hours directly into the abstract. If somebody comes and searches for the restaurant and gets the information on the first try and goes away happy, that’s terrific.

Other times, it’s the beginning of a long-running research task. You get a little bit of a richer abstract; it tells you more about what’s going to be at the destination and you can make a more informed decision about going there. When you go there, you know more about what you are getting. We expect this to be of value in both of these use cases.

Eric Enge: Let’s expand upon the restaurant example a little bit. Many publishers have become so focused on the notion that we are trying to drive traffic to our Web sites. But, if you are a restaurant, you are trying to get customers; and if you are removing a click for the customer and getting the answer they want, the chances that you get that customer for your business just went up.

Andrew Tomkins: Yes, I think that’s exactly right. There are some things that it makes sense to push upstream into the search result page, and there are some things where that doesn’t make sense. It makes sense to give the right information, to help the user more effectively navigate downstream into the rich resource. We want to support both, coming at it from the perspective of long term user value; seems like exactly the right thing.

We have worked hard to understand the value of showing an abstract like this. There is a very fine line between somebody getting their search answered without needing to click further and somebody abandoning. Pursuing this path from the search engine standpoint involves the development of some new thinking around metrics and measurement to understand exactly where this technique brings value.

Eric Enge: The other major scenario you talked about is when someone is in a research mode. I am going to take that to a shopping context again for a moment. If someone has decided they want to buy a digital camera and they don’t know which one yet, they will want to go through some process. They may generally do several research steps. Through the structured data approach, you can better represent the content on a page, helping people understand what they are going to get from you, and making sure that people who want that can see that at the search engine level.

Andrew Tomkins: Yes, right. You could almost see it as an application that the publisher is providing that is reaching it’s tendrils out through the Web and surfacing partially through the search engine.

Eric Enge: Right.

Andrew Tomkins: We talk a lot about task completion and user productivity, which is really what we think is going to drive changes in search and in everything that’s connected to search over the next few years. From a task completion standpoint, it’s great if the right answer is the right application that’s going to solve the information need or get the user going on a next step.

Hopefully, it engages the user and pulls the user in; maybe even in a more contextual fashion to the next stage of the task, where it takes place off search and thus the user continues to work through whatever the long-running task may be. They may go in and out of search many times over the course of trying to complete it.

Sometimes users do continued dives along the same subtask and other times because they’ve finished one part of the problem and they are ready to move on to the next part. They know that they want to buy a subcompact camera because they’ve researched some great sites that have really good material about what the different types of cameras are, and what types of consumers would be interested in each one.

Now they may want to know what the subcompact cameras are that they should be interested in and who are the best vendors to buy from, so we would like to think of search migrating to be able to support the whole task. The best way for people to get their task done is to be in and out of search or what we like to call getting you from “to do” to “done.”

Eric Enge: There are a few standards that you talked about that exist, that you are looking at for getting the structured data. Can you talk about what those are, and a little bit about how they differ and how they are used?

Andrew Tomkins: Yes. There are two parts of this puzzle that we like to think about. The first part is what’s the way that a publisher can mail a bucket of bits to the search engine (the envelope) to help us understand what’s there, and the second part is what’s the vocabulary? So, how should you interpret the bucket of bits? We can walk through each of these separately.

The starting point is the envelope. We are supporting three different ways for content to be transported to the search engine. One is through different types of markup, where the publisher can embed code directly into the page that can be interpreted by the engine as standard compliant markup code.

The second is through pull APIs, where the search engine is able to reach out to the site directly and has been given specific information in the form of an XSL rule about how to find relevant information on the page. The third is through feeds, in the form of RSS with extensions, to embed structured data into the feed.

Within the markup world, we support a bunch of microformats for things like people, and events, and reviews and so forth. We support hCard and hEvent, hReview, hItem, and access and we’re watching the space of microformats and supporting more as there is the adoption in the community. We also support RDFa and eRDF, which are forms of markup that can be generically embedded into HTML.

We then have a general framework for different types of vocabulary that we’ll accept within the markup. The different microformats include specifics about how to represent data. We also support pieces of vocabulary from a number of different sources including the Dublin Core, Creative Commons, and then specific things like FOAF, GeoRSS, and MediaRSS for media content, for your calendar and for your card. That’s what we are currently anticipating and will be supporting.

Eric Enge: Right. You are working with a certain set of partners. How many are there?

Andrew Tomkins: We have a number of partners where we’ve reached an agreement about being open, in the form of the abstracts that we are working through together.

I gave some examples in the SES New York keynote about these. If it would be interesting, I could verbally walk through those as maybe suggestive directions that we see taking.

Eric Enge: Yes. I am interested in knowing how you selected the early stage partners. Also, the role of trust in accepting structured data and when it will be open to a broader array of partners.

Andrew Tomkins: The way this works is that once the publisher gives the data, then it’s available in the case of feeds and markups inside our search engine or it’s accessible over the Web, in the case of the pull model through XSLT. The third-party developer is then the publisher who should have a deep understanding of the right way to render an abstract.

Another third party who has insights into the domain is then able to write a small application, which will pull out the metadata whenever a URL from the publisher shows up in the result page and create a custom abstract that will plug in pieces of structured metadata in the right place. If it’s a restaurant, it could plug in the ratings or it could plug in the price range and phone number.

That’s the scoping in terms of how we see the ecosystem working. The next thing to touch on is that we anticipate there are going to be application writers who create an abstract from a particular perspective. For example, maybe it’s somebody who is very technical; who thinks wouldn’t it be great if whenever I saw a URL from a certain place, I was able to get some very detailed technical information right in the abstracts.

We want to enable that, but it’s probably not right for all consumers. We are imagining that the standard operating environment for these rich abstracts will be a gallery, hopefully, a big gallery with lots of different ways to see results from lots of different metadata underneath it. Users would be able to subscribe to the things that make sense for them.

We’d work through all of the different ways that we have available to make it easy for people to turn on the kinds of abstracts that they want to activate. At the same time, there may also be some cases where we look at the abstract and we determine that it’s going to bring value for all of our customers to have this richer presentation.

In those limited cases we might actually have the rich abstract show up for all customers as opposed to just the ones that have subscribed to it. We haven’t announced any decisions yet about what the circumstances are going to be where we’ll do this. What we have talked about is a set of examples that we think are compelling examples that bring a lot of value.

Eric Enge: Okay. Those examples are?

Andrew Tomkins: With the partners we have, we’ve agreed to an abstract format that I’ll walk you through some examples of, although it’s not a complete list. In the Bay Area, I think a lot of people go to Yelp for information about a restaurant. I have an example from Yelp that has three pieces to it. One is a small piece of multimedia showing a picture of a restaurant so that you can verify we are talking about the same place that you’re considering.

Then, there are some deep links in the abstract to go straight to user reviews, photos of the restaurant, and maybe even some action links like send e-mail to a friend. In place of the abstract, there is actually some structured content showing ratings, address, phone number, and price range.

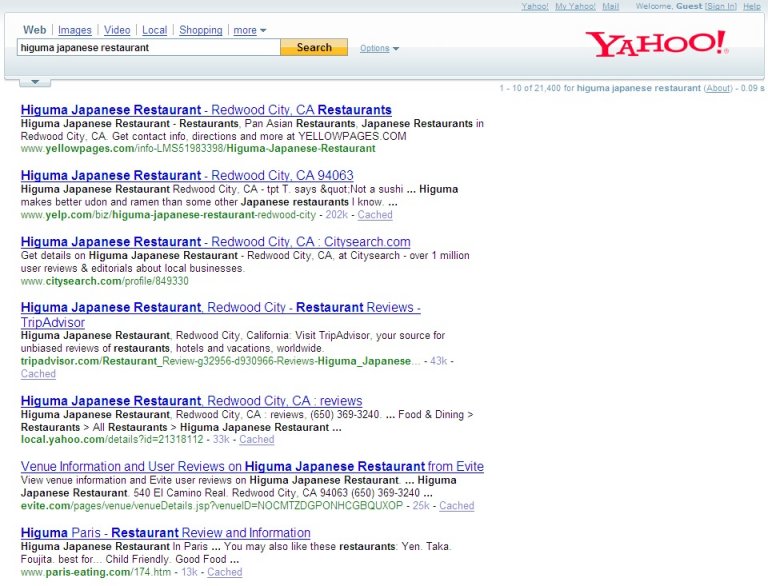

Editor’s Note: Here is a before and after picture for Yelp search result for an individual restaurant. First, note the traditional look of the Yelp search result (the second one) in our “before” screenshot:

|

Editor’s Note: And now the “after” showing just the enhanced Yelp listing:

|

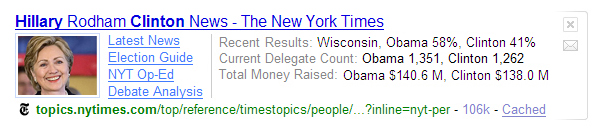

That was one example of an abstract that I used in the SES keynote. At a high level, I walked through some examples on topical information from BabyCenter, recipe information from Epicurious, question answers from Answers.com, and some news examples from The New York Times and Gawker media. When searching for people, I showed an example of a profile picture along with information like location in the abstract, for people who have chosen to make that information public with services like LinkedIn.

Editor’s Note: Here is a SearchMonkey search result for the New York Times:

|

For a medical example, I used WebMD to show some richer information about allergy content with some carefully chosen deep links into the WebMD site that link you directly to relevant parts of the allergy portion of the Web site.

Eric Enge: Right. So, like the Epicurious example that you gave, it’s interesting, because that’s a case I think of an advertising-supported Web site; and if you give the user the answer and don’t get the click, then you don’t get to show your ads, right?

But, to take the counterpoint to that, if you have a site like that where you are building a brand and somebody wanted an answer that was provided simply in an abstract, they probably weren’t going to be clicking on an ad when they got to your site anyway. And, they are going to remember that you provided the answer, certainly if it happens, a number of times. So, there is a little bit of how does it fit the business model of a particular site to be considered here too.

Andrew Tomkins: Yes, absolutely. I’d just say when it comes to sites that have an advertising business model, the goal here is to drive you to the advertising. It may be that there are types of rich abstracts that are meant to be engaging to the user, because of the type of content that the site wants to pull together anyway, or it may be that there are rich abstracts that make sense for the site, because they are looking to build a following and build a community in order to grow the user base.

I’d say it doesn’t seem clear right now exactly what the interaction between business model and richer abstracts will be. But, there is a lot of flexibility in the format. Whatever their particular preference of a site is, they can probably start to tailor abstracts to try to meet the need.

Eric Enge: Do you have concerns about people building abstracts, which were not representative of the actual content?

Andrew Tomkins: We do, yes. We actually view this as being part of the evolution of search in which whenever we start to expose new capabilities, we have to go into it with our eyes open that there are probably going to be people out there who will be malicious. We need to be very careful about how exactly we decide what to show, when to show, what to approve and so forth. I think the purpose of an abstract is either answer the question or give somebody richer, better information about what’s going to be at the destination.

The misleading abstract is one that doesn’t do those things; particularly it’s click attractive and it draws clicks to a bad end experience. Part of our process will be trying to understand what exactly it means for an abstract to improve the overall search experience, and then promote the ones that do, and demote the ones that don’t, just the way that we would in ranking.

Eric Enge: Right. Presumably, there are things you can do like read the abstract and crawl the webpage, so you can do some basic match checking there. Presumably, you can see if the bounce rate is extremely high, and there are various flags that you can look at, each of which has their limitations, but cumulatively you can get some sense as to what’s going on.

Andrew Tomkins: Right, yes.

Eric Enge: When will this be visible in different search results?

Andrew Tomkins: We have not announced a release date yet.

Eric Enge: Fair enough. Is there any general guidance you can give like during the course of the year?

Andrew Tomkins: We’d say coming soon.

Eric Enge: Coming soon to a theatre near you. Shifting directions a bit, I’d love to get your impressions on the whole notion of personalized search and what’s the scope or the opportunity and the potential impact and validity of that as a concept?

Andrew Tomkins: I talked a little bit at the SES Conference about personalization. I’ll echo that sentiment as a starting point, which is that personalization is pretty hard. There is so much work that’s gone into ranking. There are hundreds of years of research, and data gathering, and tuning that have gone into generic person independent ranking functions. It’s very difficult to develop a personalized ranking function and do better than all of the weight of history that’s gone into the independent version.

So far, we haven’t really seen a personalized search engine that just knocks it out of the park. In the future, I guess 10 years or 15 years down the road, it’s hard to imagine that we are going to give the same results to a priest that we give to a baseball player, and so forth. It seems as though there is value to be had, particularly in the context of all the work that’s gone into ranking functions. But, I honestly don’t know when we are really going to see that work for the public.

Eric Enge: What timeframe do you imagine that things might unfold at the level that you were suggesting that the priest and the baseball player would be getting different results?

Andrew Tomkins: At this point, it’s not all clear to me. Partly there was an onus on the part of the search engines to be sensitive to issues of personalization. You personalize based on what you know about somebody, and so you have to be very careful to be transparent about what that is, and make sure that you are very clear in your policies, and that your user understands what’s going on.

There is ongoing dialog around the right way for us to personalize, but I think it hasn’t been worked out yet. And, until we really understand the outcomes of that, it will be hard to understand the timelines, because it’s not just a technical question.

Eric Enge: Right, okay. One simple form is when you are in Seattle and you’re searching for pizza. You might tend to show some local results from Seattle based on GeoIP Lookup for example. Isn’t that personalization?

Andrew Tomkins: Yes. I think using location as a cue is probably the first obvious way to differentiate results. This is pretty unambiguously valuable and pretty commonly used. For logged in users who have shared a location, there’s a lot you can do that brings them more value, which is great. I guess I would expect that to be a pretty common capability.

Eric Enge: Right. Is Yahoo doing that now?

Andrew Tomkins: Yes. If you are logged in and you have set your location; then there are places on the network where we use that information, including within search.

Eric Enge: Right. What are the kinds of things that you think might happen to increase relevance? What really are the frontiers in terms of improving the ability to get the results in the right order?

Andrew Tomkins: What we believe is that improvements to relevance are going to come from the marriage of two pieces of deeper understanding. One is the deeper understanding of what the user is trying to get done. And, the other is the deeper understanding of what the content is providing. That’s probably the one step in this technical characterization of what our task completion strategy is about. We view this as content analysis of the pages that are on the Web with an eye to understanding what these pages might be useful for. Then, the ability to be discriminative in choosing which ones to surface based on where the user is in their task landscape.

If someone is trying to find the homepage of a hotel, it would mean that we have to understand that this is a circumstance where they are looking for an authoritative page versus an aggregator page. A user might also be on an informational task, and we understand that showing them a Web page that’s a navigational destination page isn’t the right track.

Eric Enge: Right. You’ll be looking at where somebody is in their task process. We are talking a bit about personalization again right because you have to have some sense and idea of where they are in their task process to do that.

Andrew Tomkins: Well, it’s not necessarily implied; it may be that you just understand the query more deeply, or it may be that you understand beyond the query. Perhaps someone typed in a query and didn’t get what they wanted and then they reformulated it.

To address this, Yahoo! recently announced Search Assist, which drops down from the search box on the results page when it senses users are having difficulty formulating a query. Search Assist offers ways for users to change their query to either dig in more to a particular concept, or expand out the particulars of what they are looking for. That may lead them to do a follow-on query, and it may be helpful for us to select results in light of what they just looked at. We know that they weren’t satisfied by the more general query and that they are looking for this more specific thing, which helps us understand how to rank it better.

Eric Enge: Right. So, someone types in diabetes and the Search Assist realizes that’s too broad a topic to likely satisfy the user, so it will offer alternative queries that will tend to lead them in the right direction.

Andrew Tomkins: Exactly. Then you can do one of two things; you can either say “offer a more specific query”, and have some understanding at what people are looking for when they enter this more specific query. Or, you could leverage other recent queries to decide what the best thing to show might be. This information will be input into the way you choose to do your query processing.

Eric Enge: If someone types diabetes, and then immediately clicks on the Search Assist link. I am not performing psychoanalysis to prove what I am about to say, but your sense would be that they just started this search because they started with an extremely general term, because they likely didn’t know how to do the more refined search, and immediately went to the more refined search. So, you might provide results that are a little more introductory.

Andrew Tomkins: Exactly. In general, I’d say that understanding the level of specificity or generosity of the researcher is interested in, is an important part of giving them the right answer.

Eric Enge: Let’s talk about something I have noticed in just doing some examinations over time. In fact, what I was doing was specifically looking at a variety of skin diseases. I would take the skin disease name followed by the word photo. The results that would come up would not always have photos embedded in the Web search result. I noticed this across all search engines by the way. It is curious to me because that’s a very powerful trigger word.

Andrew Tomkins: Yes, it sure is. When people are trying to get something done, there are often cues like that in the query. It could be something like a trigger word; it could be something particular structural about the query that’s more than just a sequence of tokens that we can understand a little bit more deeply.

Whatever it is, we view the job of the search engine is to come up with some internal representation of what the task is, and how that would be the signal that drives how we get the answer.

Eric Enge: Right. What about on the part about better understanding what’s on the site?

Andrew Tomkins: There has been a lot of interesting work in the research direction, and understanding sites rather than pages. It’s not even obvious what a site is, so that’s the first question to ask. Do you view blogger.com, or geospace.com as a site? Probably not, but in some cases, there are multiple hosts that actually are created by the same person or owned by the same person. Maybe those together are a site. Once you understand that part, you need to dig into what does the site have to say to you.

There has been great research done on understanding the template structure of a site, and what that tells you about it. This work looks at how people like to revert to the site where they enter, and what they do when they get there, as well as what are the places that seem to be engaging.

There is work on segmenting sites based on the topic or regions, say one part of the site really seems to be focused on bicycles whereas that other part is focused more on canoeing. All of these things are cues that give you a richer understanding of the content than in many cases we have today in a search engine. I am viewing them all as being very valuable from the standpoint of task completion.

Eric Enge: One complexity that you dive into is you can have sites that are very broad and cover a number of different topics. This relates to your question about what really is a site. You could have a subsection of a site, which is about one topic in a focused fashion, and presumably, there is some linkage to the rest of the site.

You might have a section of a site, which is about all kinds of products that relate to camping and articles about that, and then another one, which is about tennis. Basically, they are both activities, but they might each be rich and deep resources in and of themselves.

Andrew Tomkins: Right, yes. Understanding how authoritative a site is, then specifically for each part of the site; what they are about, how much you should trust them and how much people tend to believe them. How deep they go; all of this is very valuable from the ranking standpoint.

Eric Enge: You could have a site that has a million links, and that has many sections like I talked about, but the tennis section for some reason has very few inbound links from third-party sites. Whereas, the camping section has half a million links, where you would actually allocate trust differently by site section.

Andrew Tomkins: That’s a great example of a good cue that you would want to pay attention to.

Eric Enge: Presumably there are other cues. Another question I have is, is there a role for a touch of human review? I am not talking about trying to rebuild the Yahoo! directory as the solution for describing the whole Web, but as a way basically to search out specific kinds of problems and make corrections.

Andrew Tomkins: I think there is always a role for the human touch, and generating a full understanding of very large complicated spaces that it’s really hard to get your hands around. If you have a big distributed audience, and there is something that they are telling you then you would certainly want to take advantage of that.

Historically in search, there has been a bunch of complex, sophisticated analysis of what people are saying on a page that use complicated weighting functions to assess whether they are relevant to a query. In the end, all that is important, but it’s not as important as the simplest human signal of informally endorsing the site by producing a link to it.

Being able to understand the nature of even that very early signal has been influential for Web search. Now, we are moving beyond that into a realm where there is a lot of other human-generated signals around and available. Making use of them is, I think, key for the success of the search engine.

Eric Enge: Then, there is a whole business of the links which are given, but they are obscured in one fashion or another. I mean the list is well known; a nofollow tag or being redirected through a page which has a nocrawl on it, or obscured in JavaScript. How does Yahoo! look at those kinds of things?

Andrew Tomkins: Right. At a high level, it’s as a search engine where we have a contract with publishers of the content. We are serious about that contract; so we are looking to follow best practices. When it comes to understanding the signals that you are able to read out of this really complicated and in many ways really noisy information source. There is a bunch of complexity introduced by the kinds of techniques that you are talking about; even unintentionally.

Really understanding what it means to have a bunch of people linking in different ways to a site, for instance, is pretty complicated. When you are doing link analysis, the right way to normalize those things, and the right way to cope with pages that seem to be almost duplicates of one another, or that are duplicated but on a domain that’s within a different geography.

Maybe there are subtle cues there about how popular the content is within one geography versus another based on the linking patterns. Teasing apart what a graph has to tell you about a set of pages is a pretty delicate issue.

Eric Enge: Well, thanks a lot. I very much appreciated the chance to chat.

Andrew Tomkins: Yes, thank you!